David Sully’s Masterclass Coming Soon

David Sully has 25 years experience working with etching. Initially as a student at the Royal Academy and subsequently at an editioning studio based in Wiltshire, where he editioned prints for artists.

He is the technical instructor in etching at U.W.E and has a wide knowledge of intaglio printmaking techniques. His own practice involves drawing and etching directly in the landscape.

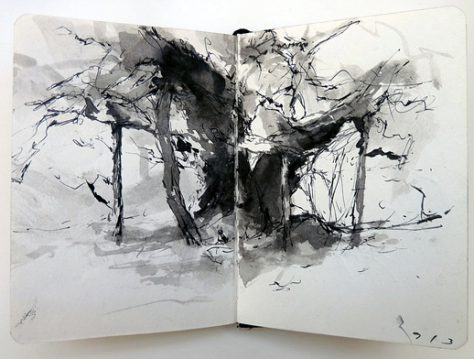

Every Lunchtime, come wind, rain or shine, David Sully and Philip Bowden (Litho instructor at UWE) walk into the woods behind the Bower Ashton campus to draw. Last year, Sarah Bodman curated an exhibition of these sketchbooks in the quiet room at the Bower Ashton Library. Here is another chance to look inside these incredible sketchbooks and hear in their own words, their motivation behind this ritual.

David Sully

It first began with occasional walks, but soon became more of a ritual with a deepening interest in recording the landscape change over time. There is an aim to note down, on a single page each day small glimpses of the landscape’s evolving history. New and old fallen trees, revisiting rotten tree stumps, seeing them decay and become monumental. Witnessing the Doomsday Oak undertake its most violent transformation over the time I have spent drawing it. The drawings as a record of its collapse and subsequent new growth.

What is the attraction? To see the moments and to hold on to them. To see the tops of the trees in Rownham Plantation coloured by a late autumn light. To see the strength and shape of the wind as it tears the last leaves from the broadest oak tree; an ascending spiral. To see the landscape change throughout the year and to see the seasons overlap, the linear architecture of the trees in winter and their transformation in the spring and autumn.

Then there is the weather. Occasional snow falling and wishing for more. A cold January wind, distant rain, approaching rain, soft light rain and of course heavy rain. Often sheltering under an umbrella suspended in the branches above. Noting the unique tone of a grey, wet day; the landscape viewed through binoculars, it’s beauty enhanced.

Then there is the wildlife. To note the swallows on the exact day they return; one year May the fourth, another May the first. Glimpses of green woodpeckers, two buzzards soaring mobbed by crows, the sound of a nuthatch tapping. In the woods, a dozen or so long tailed tits in the canopy above, often indiscernible from the falling leaves.

Perhaps the whole experience is better summed up by the nineteenth century poet John Clare, who wrote, “I found the poems in the fields / and only note them down.” It is an inexhaustible subject these sketchbooks only begin to record.

Philip Bowden

“Why on earth am I out here, doing this, again?!” When you’re miles from shelter and it looks like rain, and you’re standing in brambles and your back’s killing you and your fingers are so numb from the cold that simply holding a pencil becomes a near Olympian feat, this might seem to be a good question.

Maybe Turner asked himself the same thing as he was being strapped to the mast of a ship in order to fully experience stormy weather before painting ‘Snow Storm- Steam-Boat Off A Harbour’s Mouth’. Of course working outside need not be that uncomfortable or potentially fatal, but as I become increasingly involved with the local landscape and its depiction I find it is both desirable and necessary to be in it as much as possible; feeling the weather, watching the old dead wood rot and crumble back into the land, seeing the new growth come in Spring. This is why the daily ‘Sketch Club’ expedition into Ashton Court Estate started by David Sully is so compelling…

When I’m out in the landscape, and find a place or a subject which draws me in, something of an obsessive compulsion seems to come into play, which demands that it be examined, considered, and recorded first hand, specifically by drawing and preferably over a span of time.

Some of the drawings gathered will percolate, to be distilled later into more fully realised pieces of work, at which point the sketchbook drawings become crucial, informative material. Other drawings stand as they are, a record of a place at a particular time. Some of these places will be returned to, and as weeks or months might pass between visits, the changes that occur in the landscape become clear, and I realise why it is that I have to return, and how much I love being in the landscape.

A selection of David Sully’s etchings are soon to be on display in the SPS gallery space.